Museum-Quality Artifacts Create a Community History

Rescue archaeology at Nunalleq

This is Part 3 of a series about my experiences near Quinhagak, Alaska, at Nunalleq, the world’s largest preserved pre-contact Yu’pik site. Read Part 1 or Part 2. Listen here for an Alaska Public Media broadcast featuring the voice of yours truly.

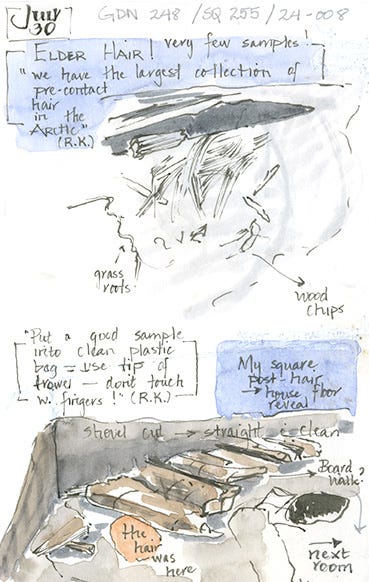

The blackish strands emerged beside the waterlogged wood boards, just slightly darker than the coal-black soil. Too smooth and straight to be roots. Too flexible to be fish bones. I was working on a layer below the burned material, so, for sure, the strands pre-dated the massacre that shut down this community.

“Hey Rick, I think I just found hair!”

I sat back on my heels, knees still cushioned by a grubby foam pad. I pushed my own hair off my face — oops, I forgot about my mosquito head net, and now dirt transferred onto it from my muddy gloves. Rick climbed out of the far end of the four by eight meter pit and walked the edge to avoid disturbing other areas in mid-excavation. Bearded and weather-skinned, rubberized overalls as dirty as anyone’s, he peered down at the edge between the wood and the mysterious strands. “Whoa, that’s gray hair!”

“We have the largest collection of human hair in the arctic,” he added. However, elder hair (gray) is much less common. It’s analysis provides dietary and health details about the person’s full life-span.

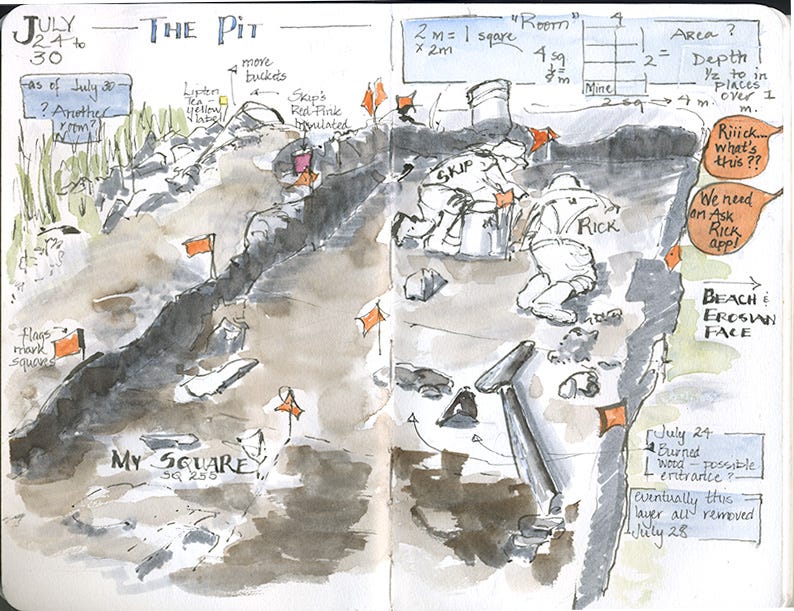

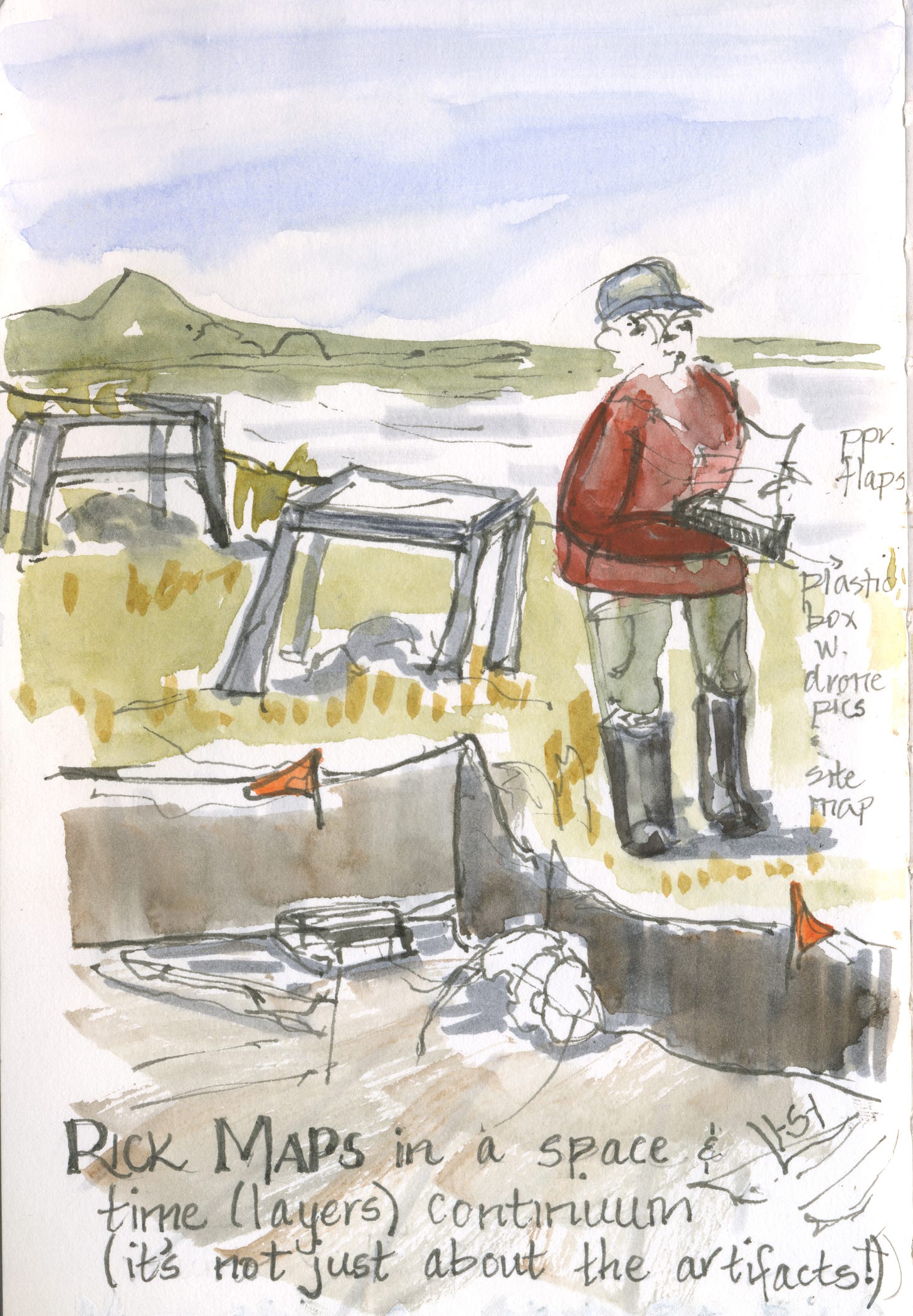

Richard Knecht is Alaska’s foremost arctic archaeologist — and the project leader of the 15-year-long rescue archaeology project at Nunalleq on the Bering Sea. He worked right alongside us beginning diggers: a collection of archaeology students and volunteers like myself who all spent a few weeks filling out the labor force before going back to our regular lives. All day long, his name flew through the air: “Riiiik!!?????” — yet another puzzling object that needed his identification.

On a more conventional archaeological dig, someone like me — a long ago anthropology major and now high school teacher/sketch artist — wouldn’t work beside the major professor. I wouldn’t be able to ask him countless questions, nor listen to his stories over ramen during a wind-break in a wall tent. And I certainly wouldn’t have found so much cool stuff — every day!

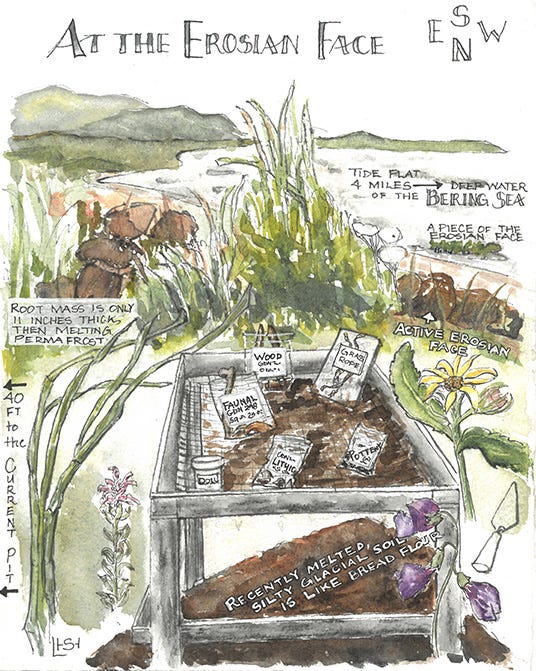

But Nunalleq is not a traditional site. The world’s largest preserved pre-contact Yu’pik site ever excavated, it faces dual threats from climate change. However, fifteen years ago, Warren Jones, C.E.O. of the local Qanirtuuq Inc., successfully argued against a long-held tradition of not digging up abandoned sites. Over 100,000 rescued artifacts and a cultural revitalization resulted.

Two emotions permeate the entire project: excitement and anxiety. The site had been inhabited for so long, then was so precipitously abandoned and thrown into a deep freezer, that, in Rick’s words, the finds trays contained at least “one jaw-dropping, museum-quality piece per person per day.”* And yet time was running out: for the dig season — which was only two months long and would be followed by violent erosion during the winter-time storm battery — and for the artifacts, which every year were more fragile and disintegrated than they had been during the first years of excavation. Rick described this as like being “in a museum that is on fire, with only our hands to carry things out.”**

For me, the excitement fed a personal, also anxious energy. I had signed up as a volunteer, with permission to take time out daily to create documentary sketches: basically, a self-funded artist’s residency. I wanted to draw every artifact I could and document all aspects of the process and scene. Yet the act of digging turned out to be so compelling that I could rarely break the spell to pick up my sketch book. I only had two weeks! Would this project, funded “on a wing and a prayer,” according to Rick, even continue? Could I ever come back?!

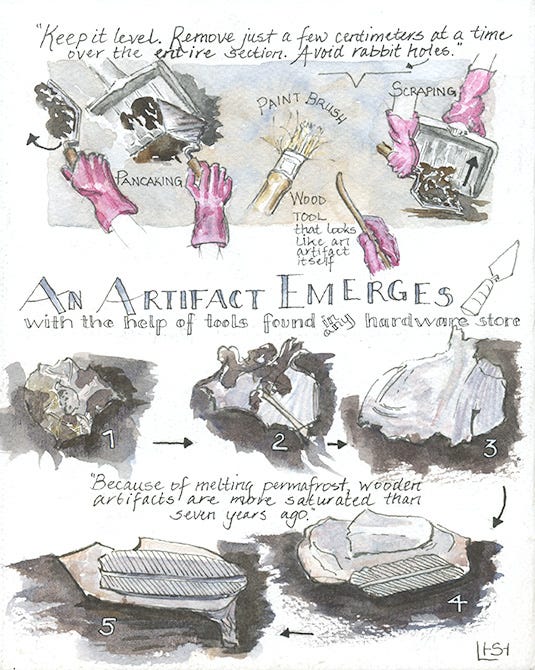

Back in my assigned two-meter by two-meter square, Rick guided me as I removed the hair without contaminating it with my own DNA. Then I returned to scraping and pancaking the chocolate-colored soil. But this time my focus was on the boards that edged the hair. The goal was to never dig more than a few centimeters down at a time, keeping the entire area level.

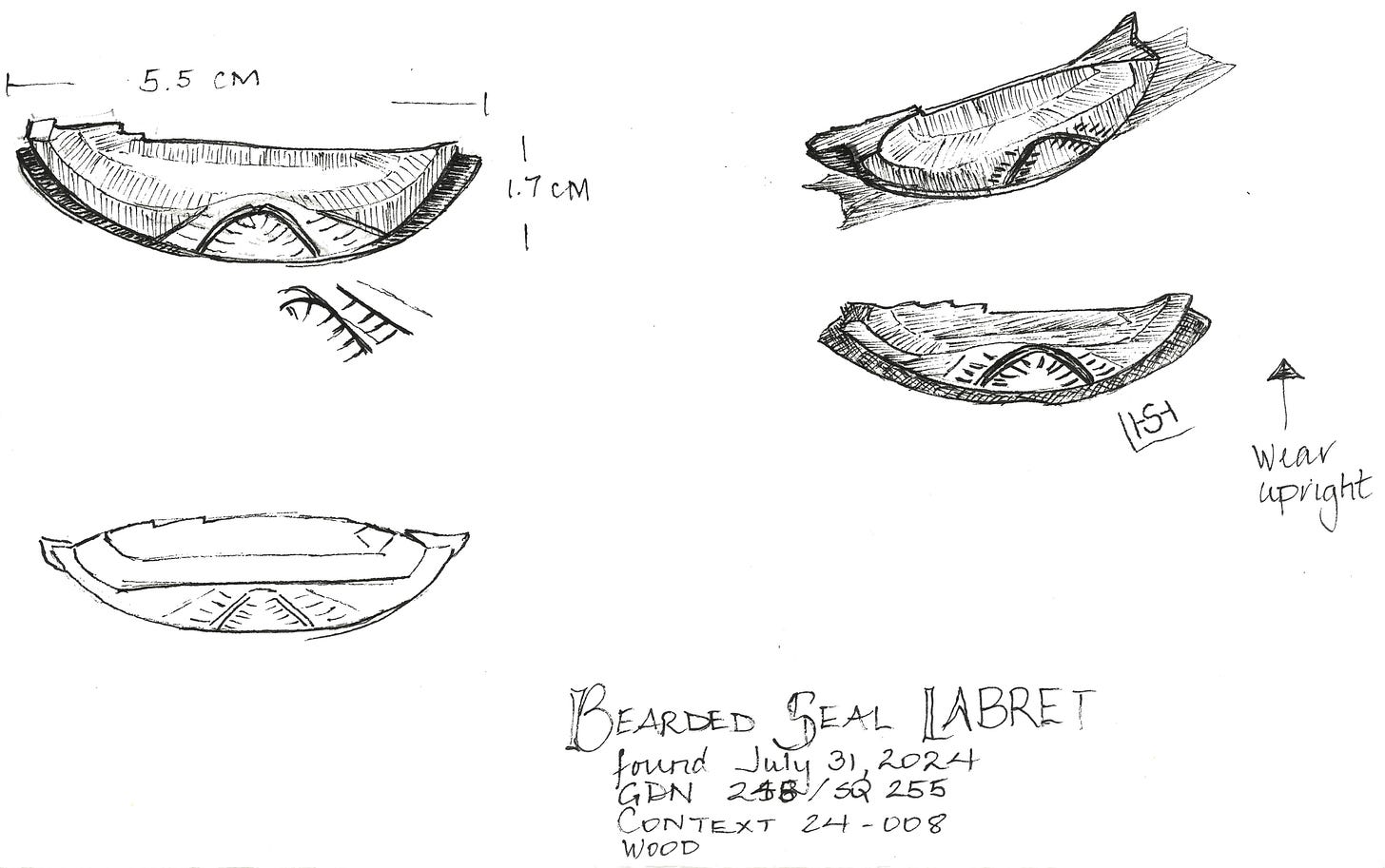

Before the afternoon was out, I also found a labret depicting a bearded seal; this particular adornment of the lower lip indicated a high status individual had spent time in this part of the sod house.

Meanwhile, Rick also determined that the boards represented an extension of the house in a completely unforeseen direction. Right there in my square, two kinds of archaeological thinking operated simultaneously — extract artifacts according to a specific protocol and use them to map a time/space continuum based on cultural knowledge. And then redraw the map when new clues appear.

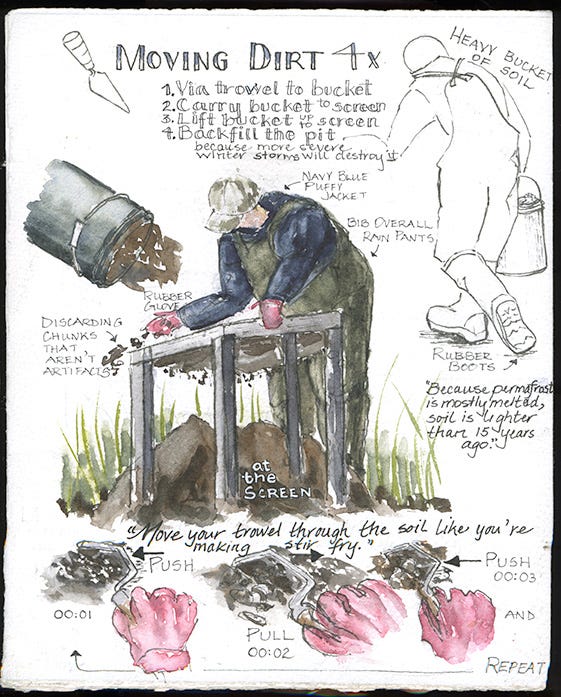

I ended the day at the screen – though I had already been there every time I had filled another two five-gallon plastic buckets. All soil removed from the pit had to be screened – you never knew what tiny fragments were hidden in the clods. Day after day, the dirt piled up below the screens — until it bumped up against the screen and had to be knocked down. But not knocked too far away. In a few weeks, all that soil would be backfilled into the pit to protect the lowest level from winter storms.

The motion for screening focused on what the soil hid inside itself. Rick compared the scoop, flip, and twist to making stir fried vegetables. In most cases, if an item looked worked in some way by human hands, it went into the digger’s Finds Tray.

My last task was sorting the heavy tray of finds into different plastic bags, depending on whether the items were Wood, Faunal (bone) Lithics (worked stone), or Pottery. Uniquely fragile items — like the gray hair and the labret I had found later — got their own protective packaging. We labeled everything with a numeric code: the site number, the square number, and the context (the age level). It all looked more confusing than it really was — and was essential for cataloging the artifacts after they were cleaned in the “lab.”

The lab is tangible proof of the other exciting outcome of this shotgun marriage between Yup’ik traditions and archaeological science. Climate change definitely brought the gun to the wedding, but now the village is in the unique position of telling its own story. In 2018, the Nunalleq Culture and Archaeology Center opened in a refurbished Headstart building: a relatively climate-controlled, wood paneled display and work space. Nunalleq is bucking another tradition, that of shipping artifacts off to universities and museums, places where the cultural descendants will never see them.

I spent that evening in the lab, drawing the labret and perusing the drawers in the display room. Still in my digging clothes, I sketched items that would normally be locked behind glass in a museum in Anchorage or even Washington, D.C.

Lise, a museum specialist also volunteering, sorted the bags of finds, cleaned items, and put the wood pieces into a preservative. This was just the first of the many hours that would be invested in documenting the finds: five hours in the lab for every one at the dig.

But all the work will happen right here in the community. School kids can hold in their hands the tools and artwork of their ancestors. Current elders can look at items used during an episode of their familial history that they heard about from their elders. Everyone can learn about the culture that existed before the missionaries.

It’s actually a perfect example of Rick’s view that people work best under pressure. Nunalleq’s inhabitants adapted to a cooling world; their descendants in Quinhagak are adapting today in their embrace of this new approach. They relinquished their traditional strictures against unearthing old sites for the cultural opportunity climate change offered. As dependent as any on fossil fuels, the changes in this environment are legion: the caribou I remember from my first teaching stint in this region are rarely available, rivers don’t freeze on schedule, melted permafrost means no storage for salmon to feed the dogs and therefore no more dog teams. In a film about the project, Jackie Cleveland, a Quinhagak filmmaker, says, “You have no choice but to adapt (to climate change) — you can resist it or do it effectively . . . but it’s gonna happen.”**

Six months on …

It’s now been half a year since I kneeled in 400-year-old mud, Bering Sea winds to my back, mosquitos inexplicably still able to swarm my face. I took the above photo at my desk, so far from Nunalleq yet still trying to quell the nervy excitement prompted by thinking about it. I don’t know what shape the project will take this season or if there’s a role for me. But for a short moment, I got to be part of something related to climate change that was tangible and concrete, something I could touch, a place I could make a small difference. All I want is to go back, to stick my hands deep in the story-laden soil and rescue a few more fragments before the future overtakes us.

*Fifteen years in, the success of community based archaeology in Quinhagak is bittersweet

**Welcome to Nunalleq: stories from the village of our ancestors (short films by Dr. Alice Watterson)

ABOUT THE ART

All the images in this post are Stillman & Birn Alpha sketchbook pages or from two foldout 8” x 30” pieces of Fabriano Cold Press watercolor paper.

UPCOMING: There won’t be any posts for a few months as I am heading back to the Chile/Argentina border, continuing a human-powered journey “north to Alaska!” (though, at the current rate of travel, we might not get there until the next century :)

❤️