Of Seals and Distant Science

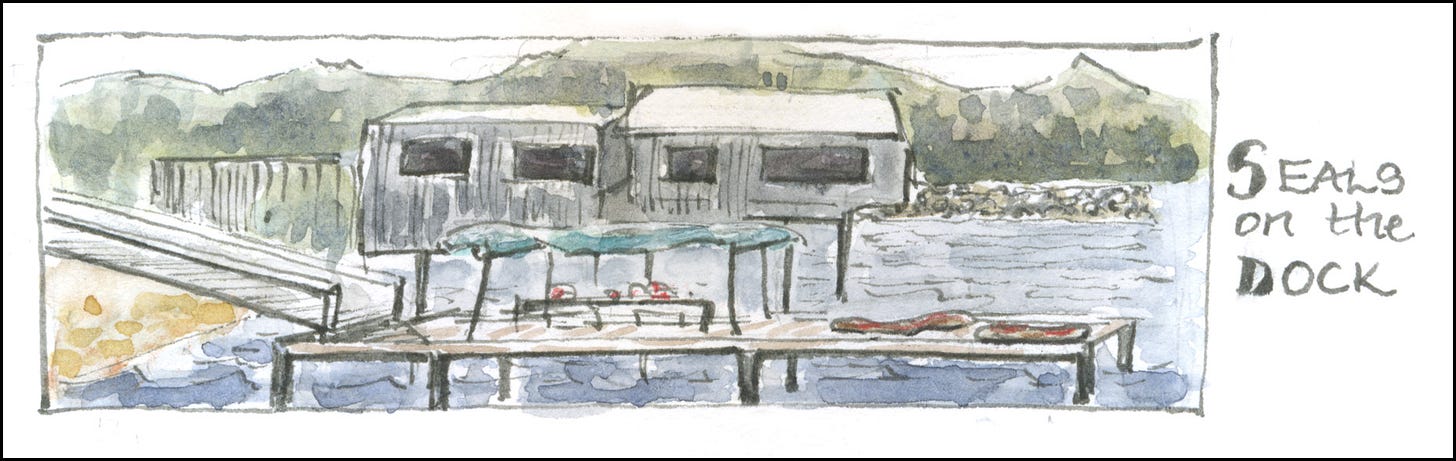

Hoonah, Alaska

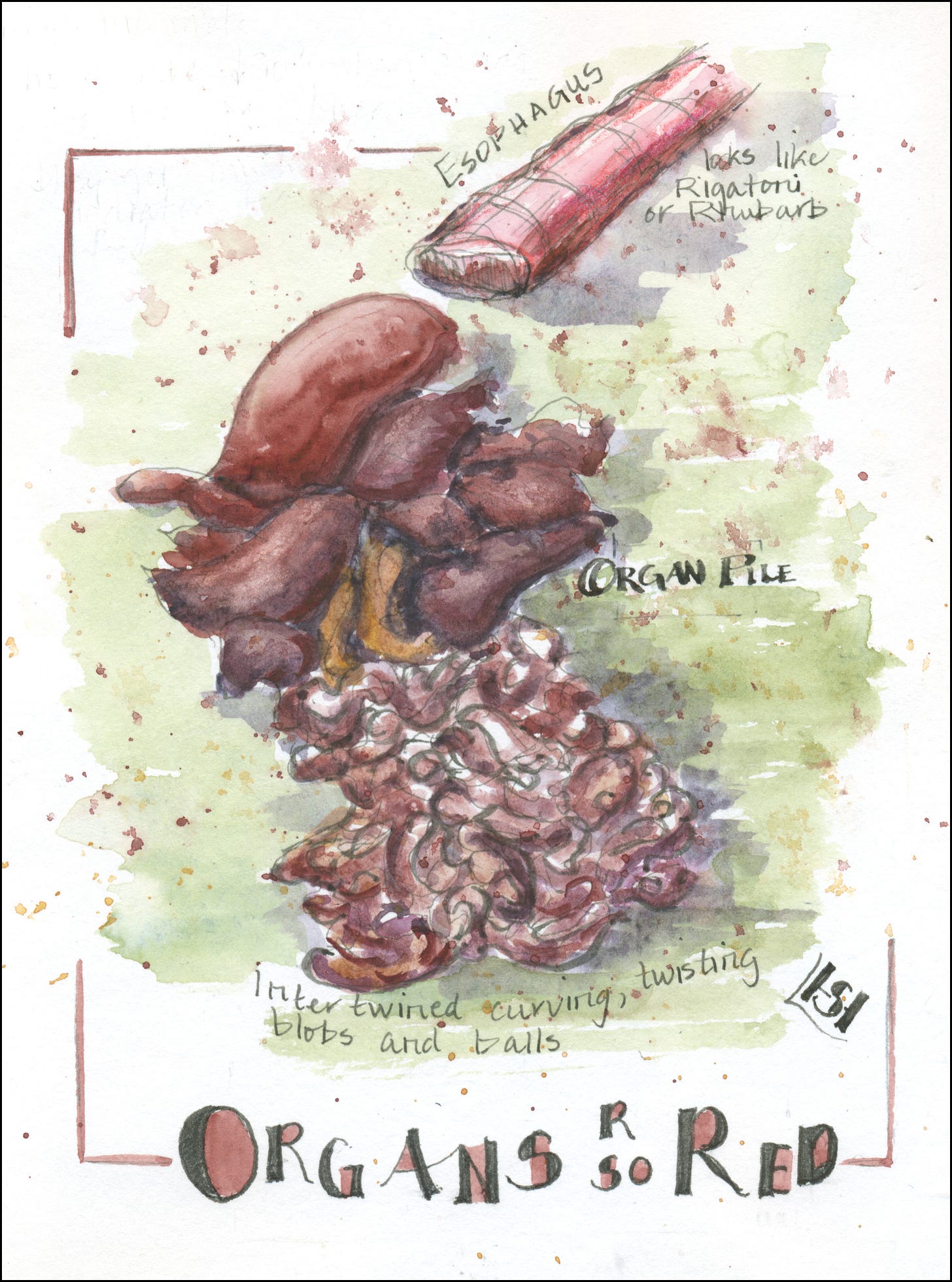

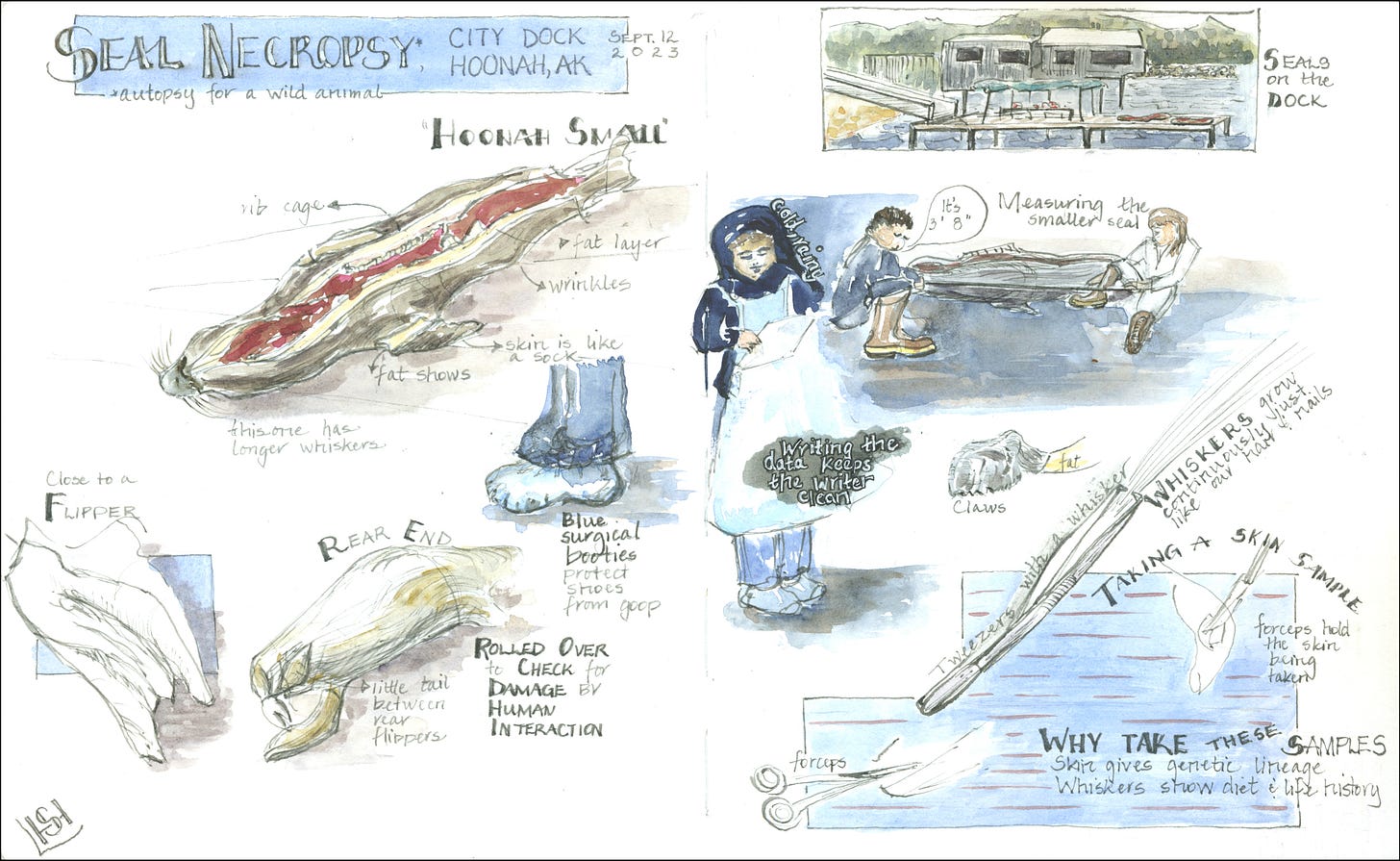

Under low clouds and light sprinkles, the nearby Hoonah Cold Storage plant rumbles, a giant refrigerator spewing fumes of dead fish. On a bright blue tarp spread over of the dock’s slick planks lie two gutted Harbor seals (Phoca vitulina.) Belly up, their rib cages, fat layer, and sock-like skin are easy to see. The innards lie already sorted into jelly-like piles on a folding table.

Twenty high schoolers, quiet with morning grogginess, circle one of the seals. The science teacher reminds them to stand an arm-swing apart because “we’ll be using knives and other sharp objects.” Meanwhile, one of the researchers explains the PPE: “Even though there’s nothing inherently dangerous, we want to avoid contact with seal blood and “mitigate exposure to zooamatic diseases.” He offers blue surgical booties to those without rubber boots — as well as latex gloves and full-coverage aprons. “We need someone to take some measurements,” he continues, “or you can volunteer to do data if you don’t want to get dirty.”

These seals are part of a necropsy — an autopsy for an animal — sponsored by the Sealaska Heritage Foundation and the University of Alaska Fairbanks. The necropsy has a dual purpose: gather data while demonstrating to students at Hoonah City Schools both scientific and traditional Tlingit methods for processing seals. As an art educator at the school, I’m here to sketch — and model an aesthetic approach to documenting an event. However, I’m also the daughter of an internationally known biochemist. I’m intrigued that I am sketching his process of the scientific method in the context of the landscape-based values of my adopted home, an indigenous community.

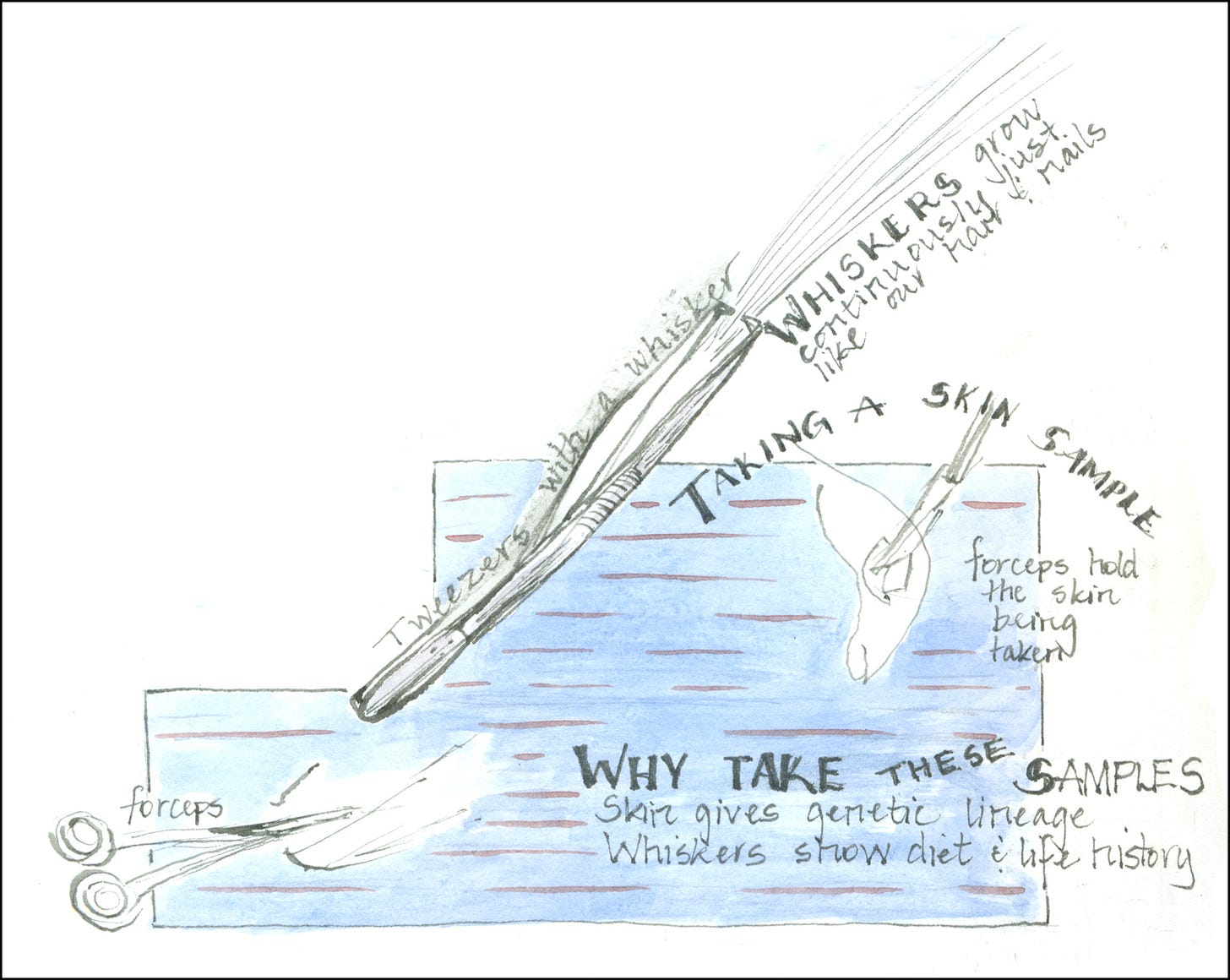

Over the next two hours, the researchers and the less squeamish volunteers gather data from one of the seals: check for damage to the hide from human interaction; measure the size; take skin and whisker samples. We learn that the skin’s genetic information will connect this seal to a lineage. The whisker, which in life helped to find prey by sensing movement in the water, will yield life history, especially dietary information. I note down the similarities between the seal whiskers and our own nails and hair: all grow continuously.

I delight in such factoids. It’s the only piece of my father’s near-religious devotion to basic research that rubbed off on me. He is committed above all to research undertaken for no specific useful purpose — knowledge gathered only for knowledge’s sake.

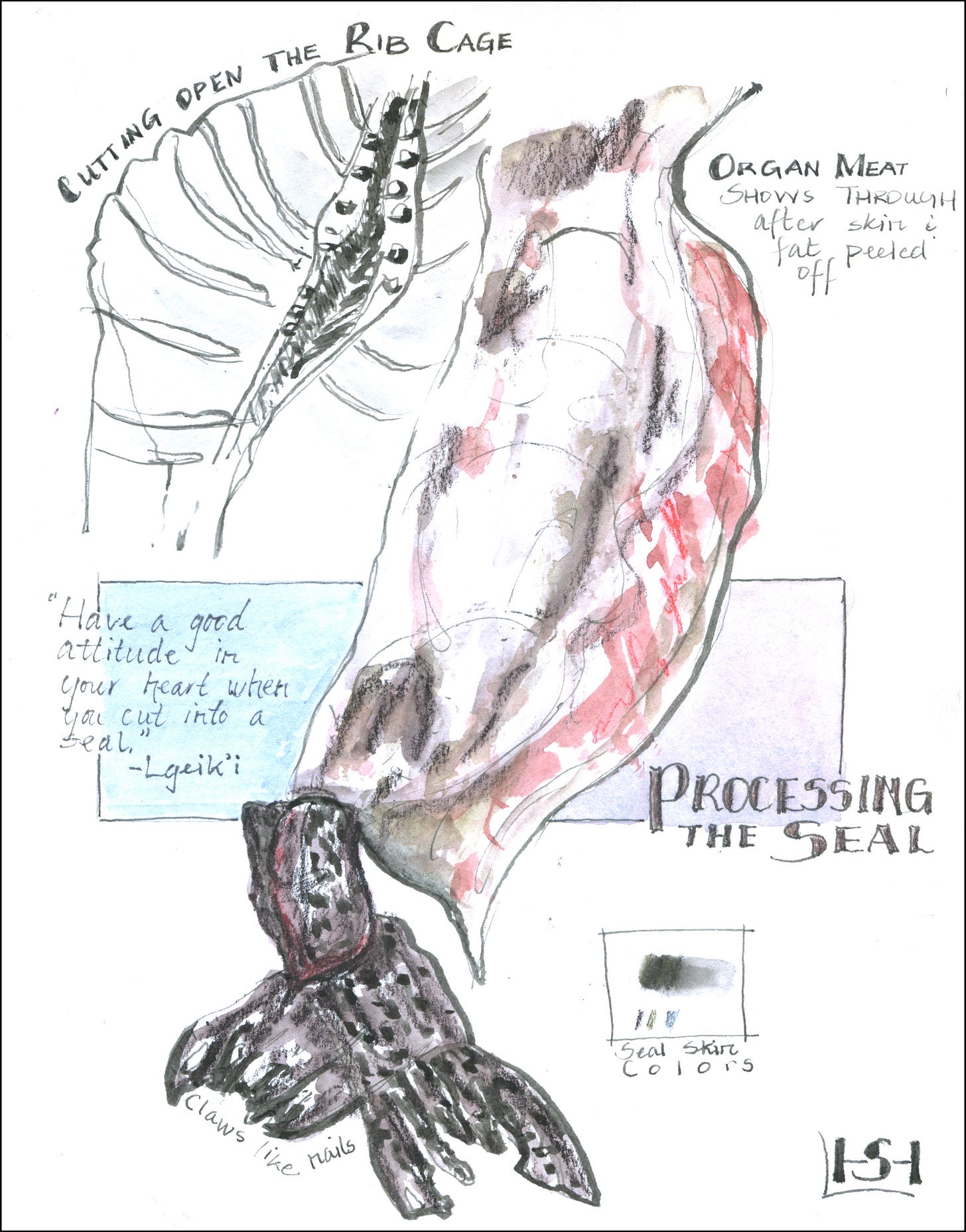

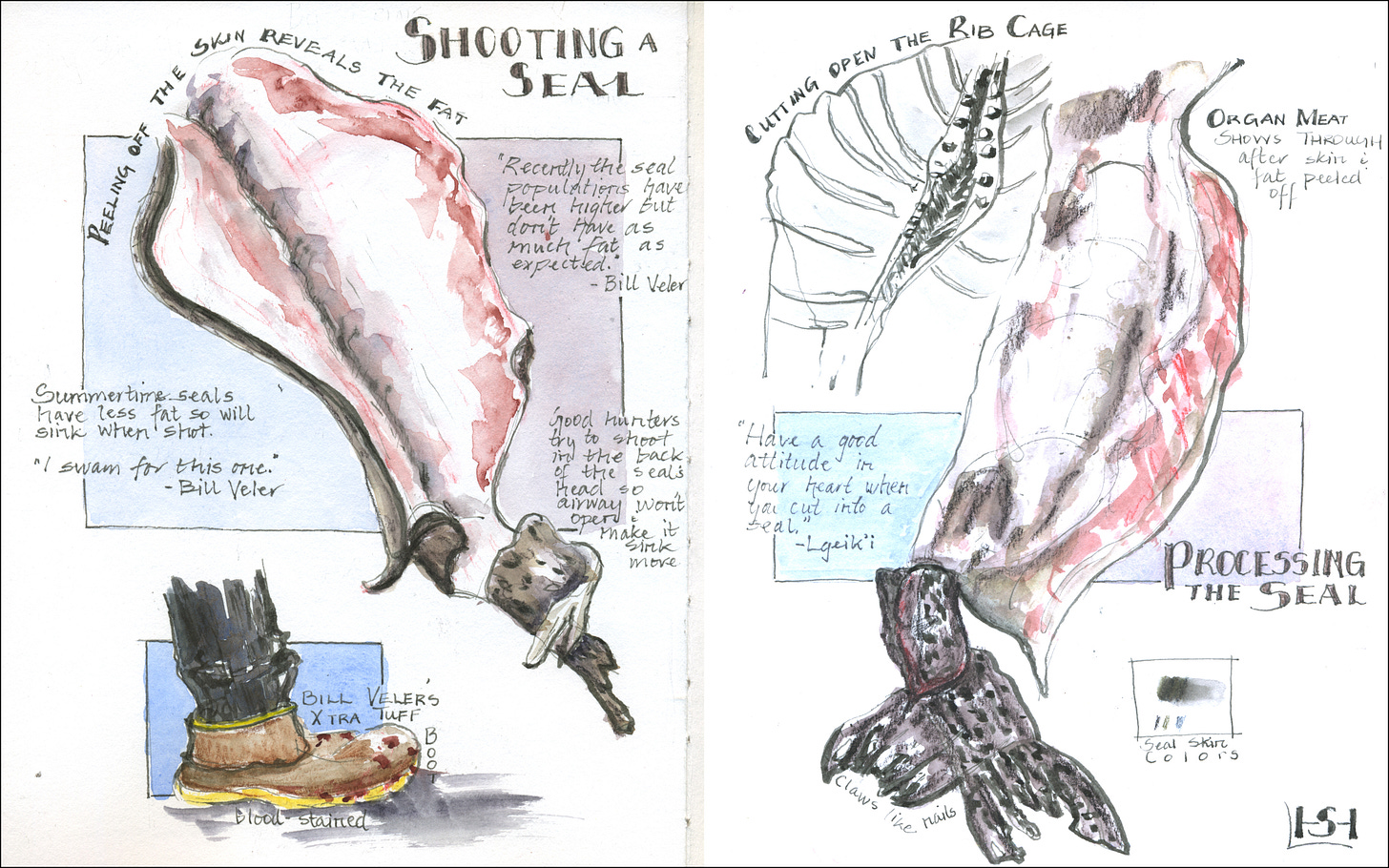

Now the hunters who shot the seals take over. Under the federal Marine Mammal Protection Act, only Alaska Natives living along the North Pacific or Arctic Oceans may harvest marine mammals — and then only for subsistence use.* The seals transition from their research status as Hoonah Small and Hoonah Large to beings who are part of a spiritual circle, the subsistence tradition of gathering and eating wild foods. That’s why the Tlingit Language and Culture teacher reminds the students that you must “have a good attitude in your heart as you cut into seal.” In a few days, the meat and oil from these seals will be given out of respect to elders who can’t harvest any more.

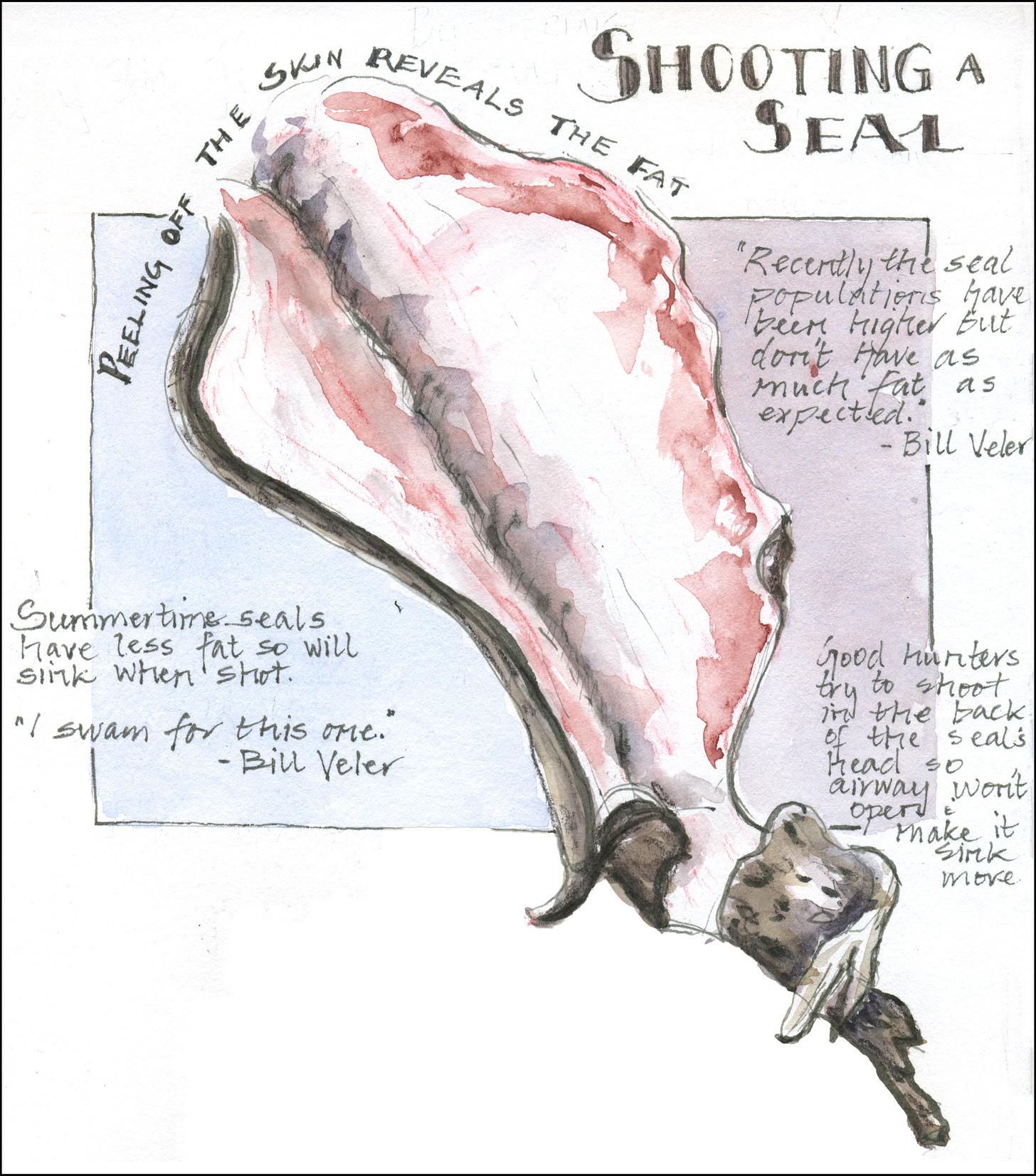

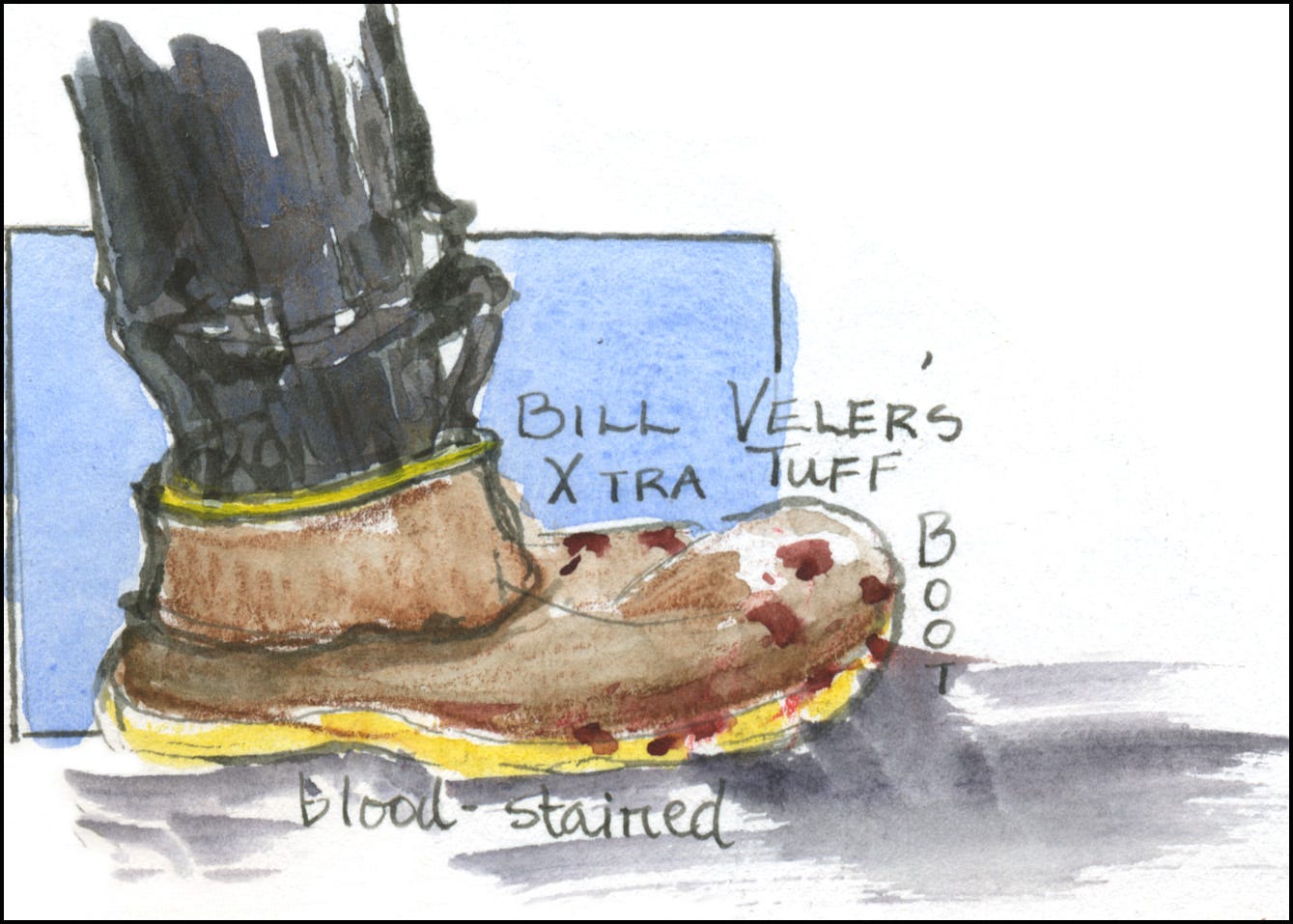

With fluid knife strokes, the hunters peel the skin off the fat layer as if it were no more difficult than removing adhesive backing from a mailing label. One of the hunters explains that when harvested in the summer, seals have less fat so tend to sink when shot. “I swam for this one,” he jokes.

One of the community’s elders is here today. He demonstrates how to call a seal. A soft-voiced, stern-faced Tlingit man, he has fed his family almost entirely in a traditional manner.

I remember a hot August many years ago when I accompanied this elder to net sockeye salmon. On the way home, with a skiff already heavy with 100 red-tinged fish, he suddenly slowed down. Fifty yards ahead, a shiny black head bobbed at the waterline, revealing only eyes and nose. “Seal oil sure tastes good with boiled fish,” he said.

An eerie croak slid from his throat. The bewhiskered head peered at us. He repeated the sound. Now the head was closer. He lifted his rifle, relaxed. Fired.

Soon we were back on shore, not far from where we had cleaned the fish. His brown hands blended into beach gravel and once again disappeared in a fan of blood.

At the time, I didn’t realize the level of skill I witnessed. Even though it was August, the dead seal stayed right on the surface. I learn today that, apparently, he must have shot it at the back of its head, thus avoiding opening its airway and causing it to sink. But I swear that seal was looking straight at us!??

With the hunters in charge of the necropsy, things now move a lot faster than when the focus was on teaching the science. I sketch as fast as I can. But I can barely keep up as the hunters cut the rib cage and begin on the meat. Blood splatters their boots and rubberized rain gear.

Their hands fly with the same ease that I find with my pen and brush — except that all I can do is visually and verbally describe, forever at arms’ length from what they simply do.

Apparently, although seal populations have been higher, they don’t have as much fat as expected. I add a few words beside the sketch to highlight that detail just mentioned. I assume the researchers take note also. But does that information — delivered in a seine boat captain’s authoritative voice and recalling a lifetime of seal hunting — count as data for the researchers?

The hunter’s statement about fat level and population is TEK, Traditional Ecological Knowledge. This is “the on-going accumulation of knowledge, practice and belief about relationships between living beings in a specific ecosystem that is acquired by indigenous people over hundreds or thousands of years through direct contact with the environment, handed down through generations, and used for life-sustaining ways.” **

The students’ attention wanders: they chit-chat and cell phones emerge. But everyone perks up for a tour of the organs. I’m still trying to document all the different hues of red in the bloody pile when the researchers package everything up. The parts disappear into waiting coolers for more analysis in the lab.

* * *

It’s been a year since the necropsy — and two months since my father died. With my brain and heart on overload, the necropsy seemed an easy topic for this post. The drawings were long done, and when I posted them last year on Instagram, several readers were intrigued by the experience.

However, in the context of my father’s death, I’m wondering what exactly the scientists found out — and why I’ve never heard more about what happened with their work. It’s as though Hoonah Small and Hoonah Large simply dissolved into the larger data pool. Of course, this is the essential difference between indigenous knowledge “rooted in the relationship between humans and their environment . . . the knowledge gained to be managed by the community,” and the science that my father devoted his life to, the quest for “universal rules that apply everywhere.” *** The problem is that my father’s science prioritizes publishing results — getting information out there where the like-minded can access it — in order to duplicate the research, verify the conclusions, refine the thinking, build on the ideas to further deepen the understanding. And Hoonah Small and Hoonah Large are only important in that larger process. They offered nothing as individuals to report back.

The seals disappeared into two conceptual receptacles: subsistence food and scientific data. The oil extracted from layers of blubber became a golden, sour syrup. Like the meat, it carried far more significance than practical nutrition. It ended up in elders’ homes and on the communal tables of cultural functions. The thing about seal and other traditional foods is the feeling on the tongue, the filling up of the stomach with the flavors and strength of the ancestors — all eaten in the same place as where those ancestors lived.

Meanwhile, all the scientific data became additional dots on graphs, significant only in their aggregate. It’s a bit like random acts of kindness — which make both giver and recipient feel fractionally better yet in no way individually change the trajectory of history.

I wish there had been a third metaphorical container — a public accounting of the specific observations by the hunters and the students. After all, the seals were our neighbors.

I wonder what my father would have said about this. Perhaps: “But, Stephanie, would anyone really care?”

I don’t think it matters whether anyone would care. Information needs to be available in its home.

* https://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=subsistence.faqs#QA4

** https://www.nps.gov/subjects/tek/description.htm

ABOUT THE ART

Below are the original double page spreads I did on location for the images in this post. I worked in an 8x10 Stillman & Birn Beta sketchbook and used Inktense Watersoluble Color Pencils and a Sailor Fude pen with Noodler’s Lexington Gray ink. I added watercolor afterwards.

NEWS

Wild Spruce Artworks, a women-owned wholesale distributor of Alaskan art, is now carrying four of my nature illustration greeting cards. Check it out!