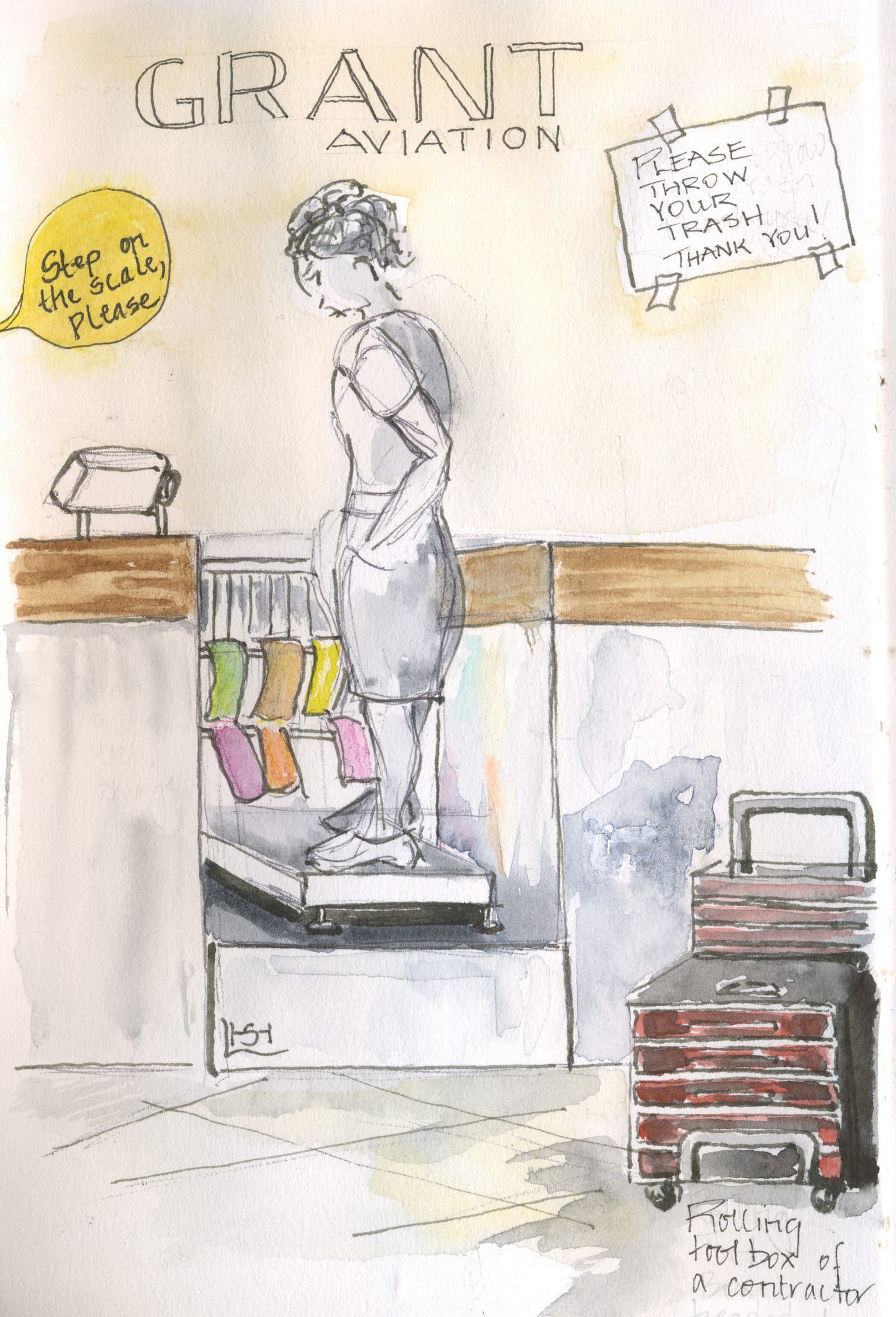

“Step on the cargo scale, please,” said the agent at Grant Aviation. He was short and dark with a face reminiscent of a Picasso painting.

I hopped up in my hiking boots, daypack still on my back. He added my total weight to the plane’s manifest.

“OK, you’re all checked in. Plane won’t leave for another hour.”

At least.

All afternoon I sat in the shabby beige building of an air taxi company servicing the communities surrounding Bethel, Alaska. Most of what those villages needed passed through this terminal: fuel, groceries, healthcare professionals, hardware supplies. I felt like a tourist in an unexpectedly foreign country. I noted the sign above the tap in the Alaska Airlines restroom — “Don’t drink water — and counted the technical contractors who arrived at the check-in counter with rolling tool boxes. As I sketched the waiting area, I pulled out the accented English words from the clucks and twists of Yup’ik. This is the language of Alaska’s largest indigenous group, cultural relatives of the Inuit of the circumpolar north.

Finally, I heard the call: “Quin-uh-hawk!”

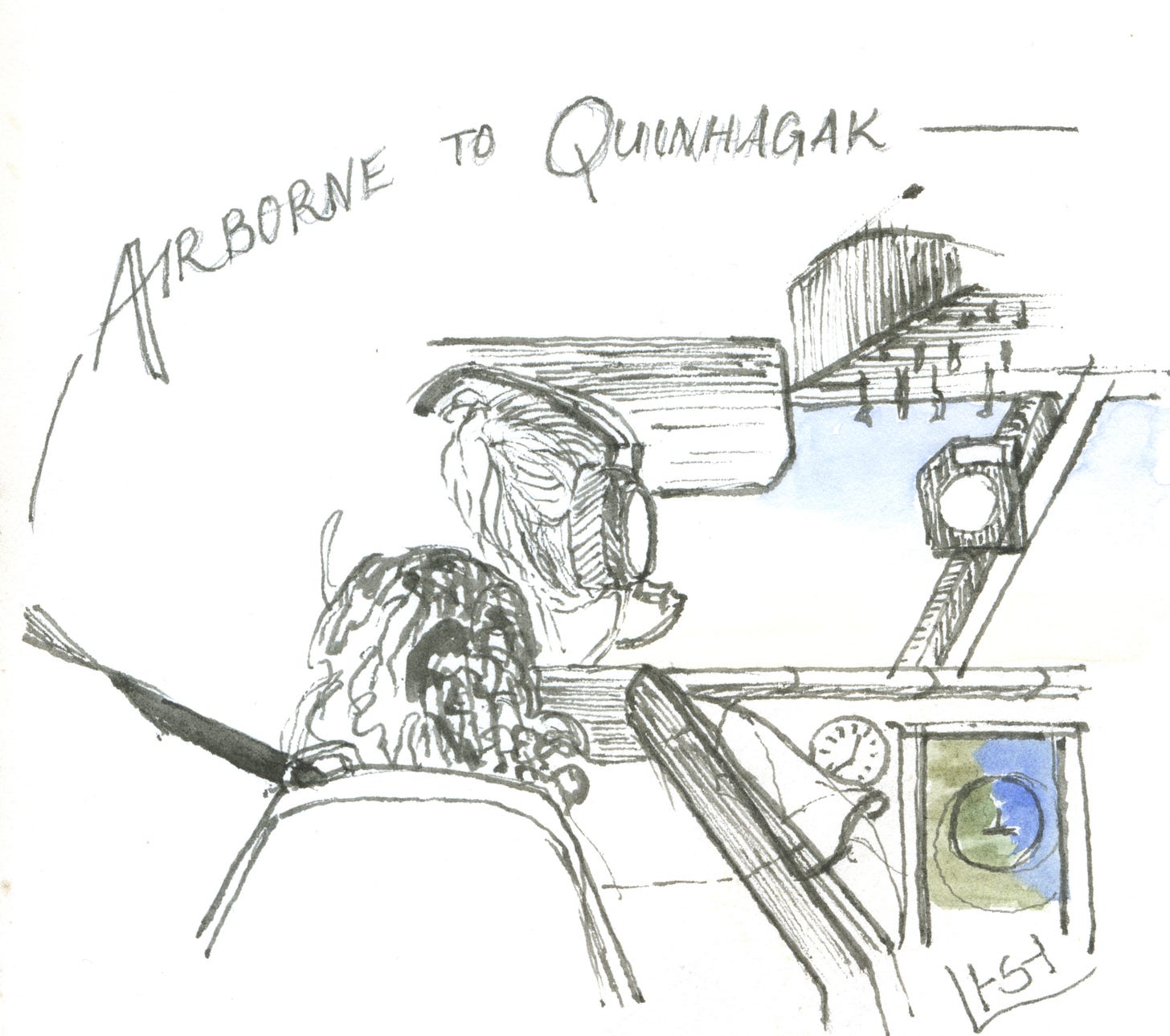

I followed the pilot out into the bright, flat light of sub-arctic July. Behind me walked two ear-budded, sandal and shorts-wearing Yup’ik teen passengers texting on their phones.

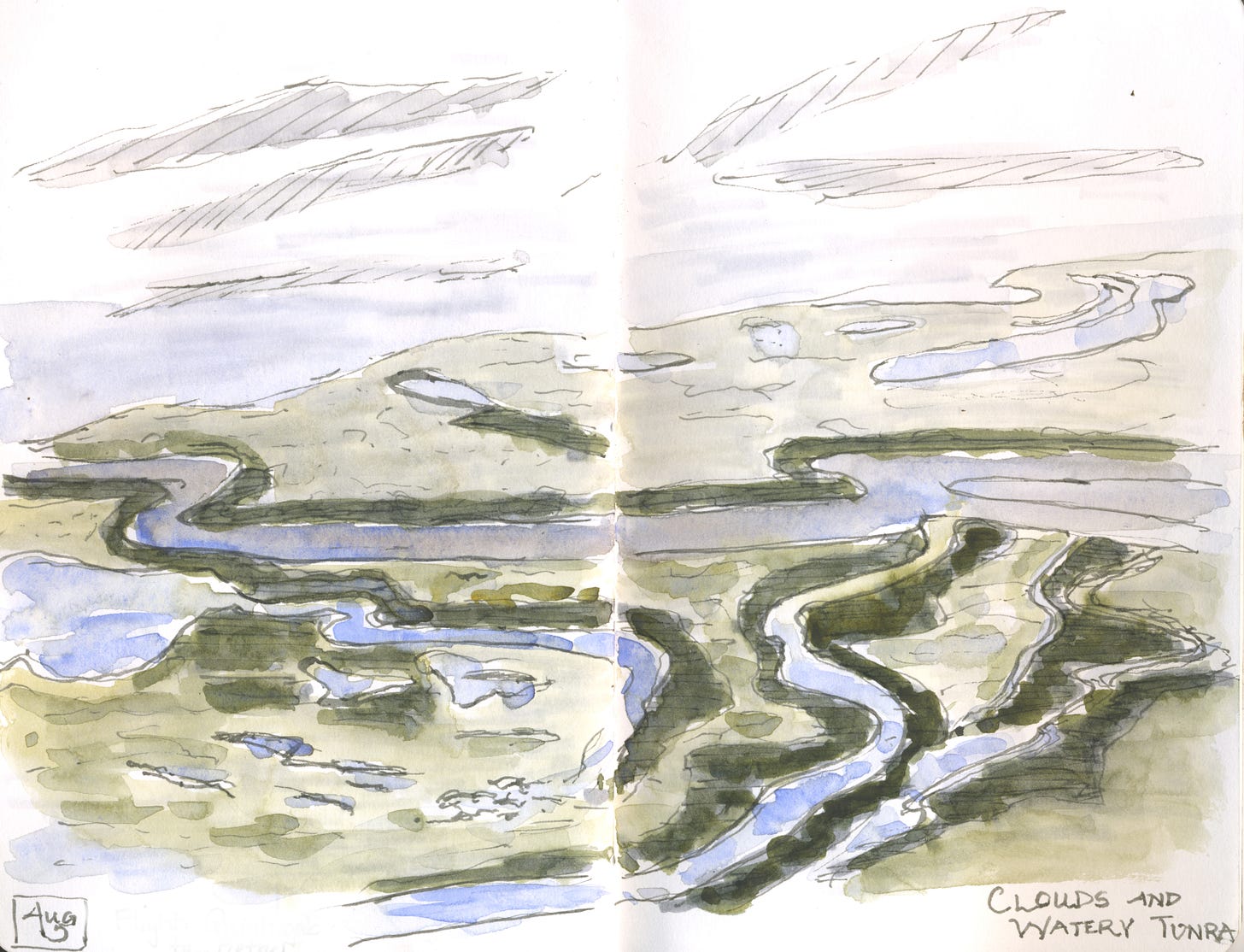

And then we were airborne, a flimsy nine-seater box riding the air drafts above a sea of curving greens pock-marked with ponds.

Meanwhile, a lake-sized river twisted west and distant mountains rested diorama-like and blue in the southern haze. Adrenaline surged against my seatbelt, an unruly, disconcerting energy supplied by all that space.

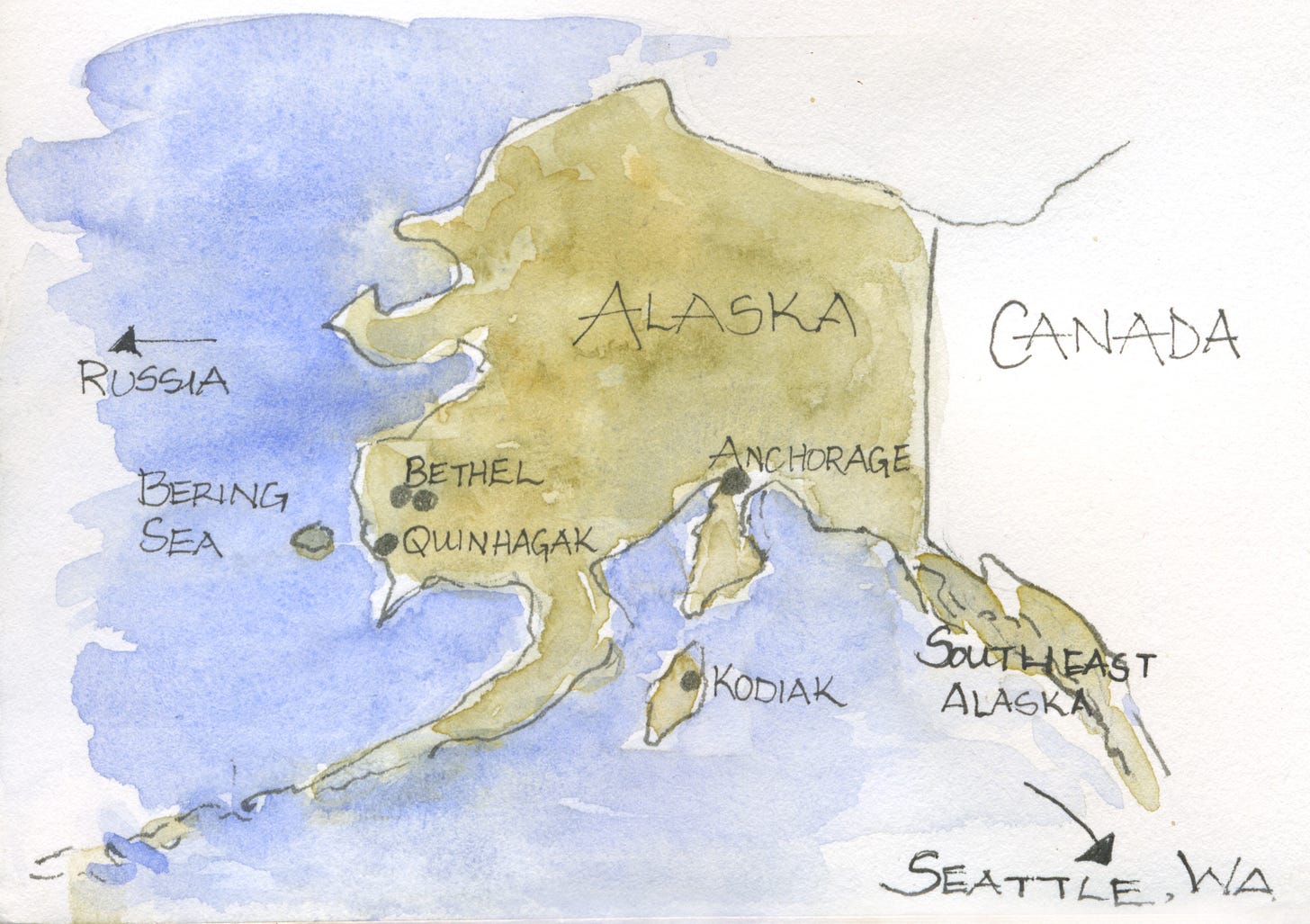

I was back in the wide landscape of western Alaska, where my husband and I had lived when we came to the state in 1991 as first-year teachers. I remember arriving in August to beach ice at the Bering Sea river mouths. Caribou came through our village as a silent chorus. Every house had a dog team tied up, fed by salmon stored underground in the permafrost. However, I wondered how much had changed due to unprecedented warming from climate change.

I was headed to Quinhagak, a 30-minute flight southwest.

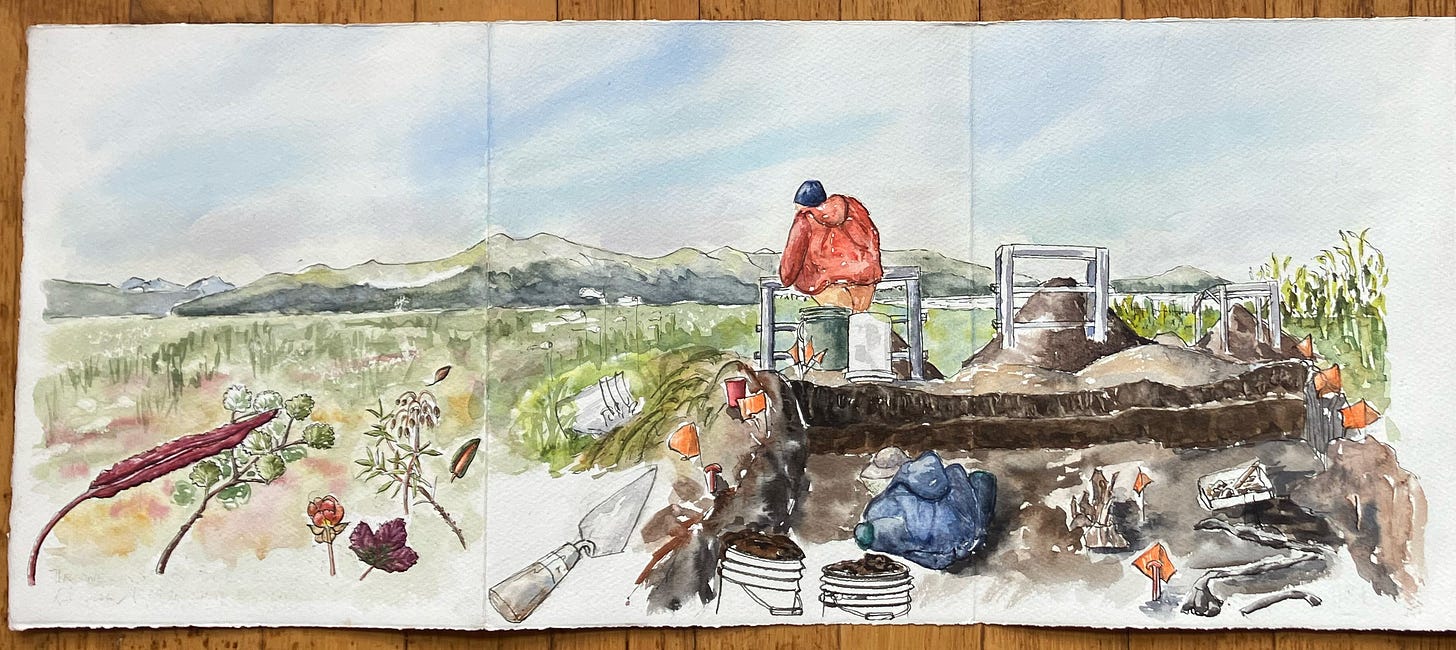

A village of 750, Quinhagak sits where the Kanektok River meets the Bering Sea. It is about three miles from Nunalleq, Old Village, the world’s largest preserved pre-contact Yu’pik site ever excavated. The site faces dual threats from climate change. Violent erosion caused by sea-level rise is washing the bread-flour-like glacial soil — and the artifacts buried within — out to sea. Meanwhile, artifacts behind the erosion face quickly disintegrate because the protective permafrost is now waterlogged. I had come as a volunteer to help with what’s termed “rescue archaeology,” an on-going project at Nunalleq since 2009.

I spent the next two weeks largely in the dirt, trowel in hand. This was just a portion of what appeared to be a massive subterranean sod house. In an ever-shifting landscape, it is located about fifty feet from a low bluff. Below the bluff runs a narrow beach, easily drivable with an ATV. The beach flanks a four-mile tide flat that drops off the horizon into the Bering Sea.

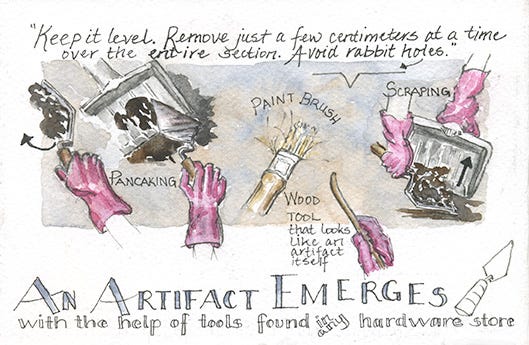

Swathed in rain gear, boots, and layers of jackets — and sunhat and sunglasses against periodic bursts of sun — and a mosquito head net whenever the wind died, I learned the archaeological techniques for following the layers within the pit.

We used tools available in any hardware store.

That simple equipment allowed us to unearth equally simple objects with which their creators had thrived in this moist polar climate: a wet tundra patchwork of endless lakes and meandering rivers, pummeled in winter by the Siberian cold arriving on the sea ice.

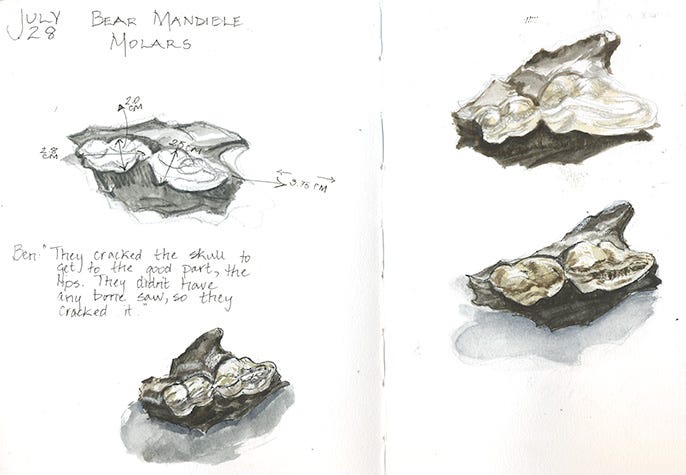

I drew artifacts at night and painted the scene whenever I remembered to stop. However, mostly I dug, dug, dug — addictive, gardening-style work that reveals what is hidden below instead of what will sprout above.

It wasn’t until several months after I left that I started putting together the significance of Nunalleq’s story for myself.

UPCOMING: Part 2 of Trowel-ing Against Climate Change on Jan. 22, 2025

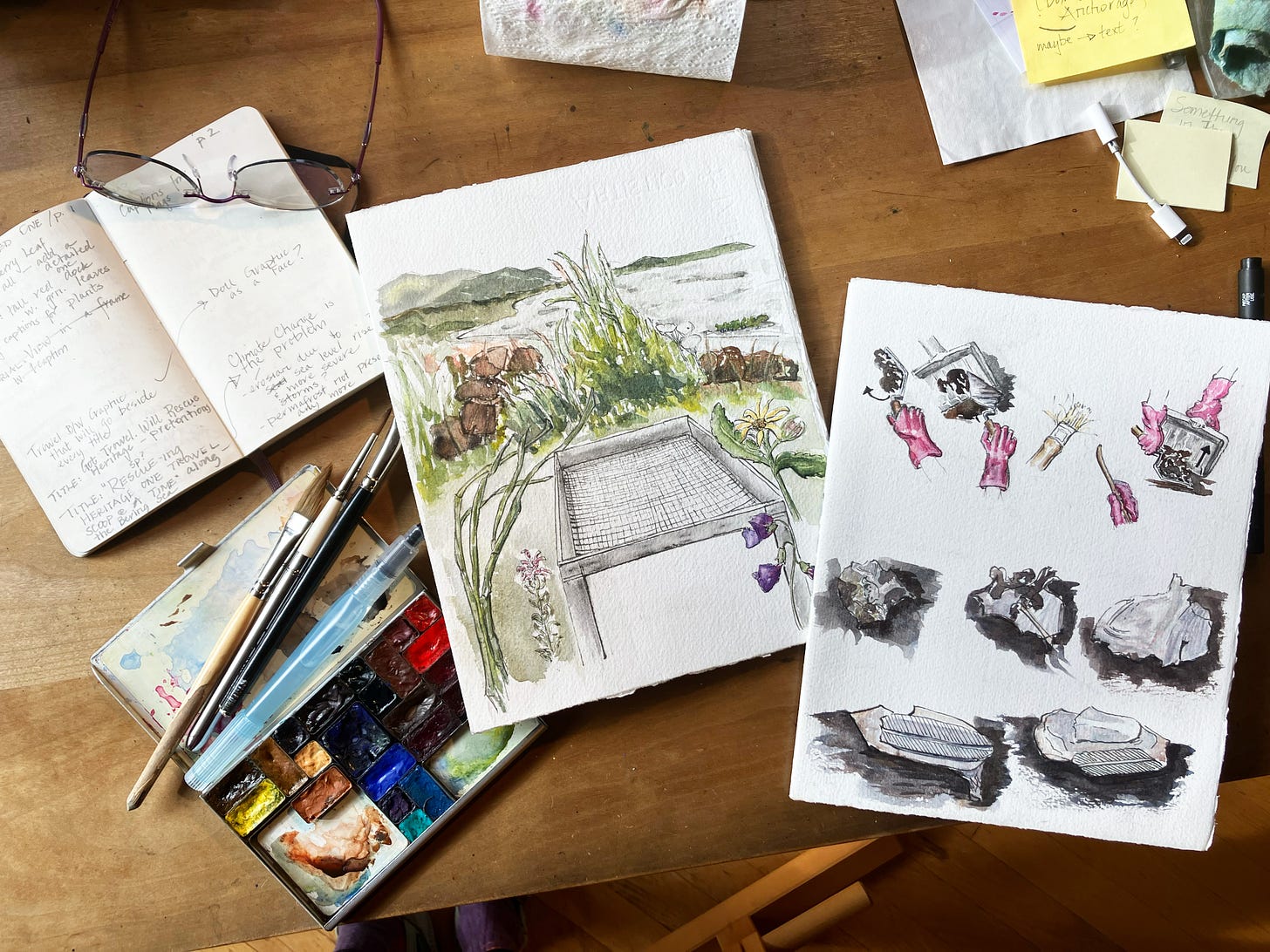

ABOUT THE ART

All the images in this post are Stillman & Birn Alpha sketchbook pages or from two foldout 8” x 30” pieces of Fabriano Cold Press watercolor paper. I use the latter because it handles pen detail so well.